[ad_1]

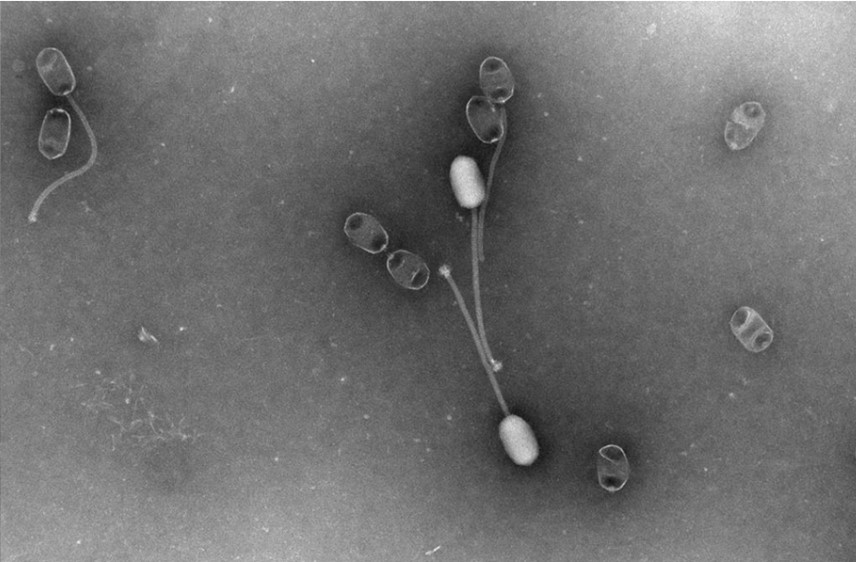

They look like something out of nightmare, but these so-called ‘spider viruses’ occur naturally, and could be a powerful new weapon in tackling the growing threat of antibiotic resistance. Bacteriophages, or phages for short, have a remarkable and currently untapped potential for viral therapies. Their name comes from the Greek for to eat – ‘phagein’ – suggesting that phages swallow up bacteria. It’s a great image, although the reality is perhaps even more remarkable: phages inject bacteria with genetic material that ultimately destroys them.

At the end of last week, the government signalled that phages are being taken more seriously as an antimicrobial treatment option in response to a report published last year – great news in the fight against superbugs. Here at UKHSA, we partner with many other organisations on research that feeds into the UK’s plan for using phages.

What are phages?

Essentially, they are viruses that hunt down and destroy bacteria. But unlike antibiotics that kill all bacteria (including the beneficial ones in our gut), phages are more precise: some are even capable of targeting specific strains of bacteria.

Phages have been used therapeutically for decades in parts of Eastern Europe and former Soviet countries, but their potential has been overlooked in the West – until now. As antibiotic resistance has reached crisis levels, scientists are taking a fresh look at how phages might provide another line of defence.

How could phages help us in the UK?

A report from the House of Commons Science, Innovation and Technology Committee, published in November 2023, highlighted the exciting possibilities of using phages more widely to treat drug-resistant bacterial infections. And it doesn’t stop there – phages could be combined with antibiotics to boost their bacteria-busting power and break through stubborn biofilms that help bacteria evade conventional drugs.

Phages could allow us to create highly personalised therapies tailored to each individual patient’s condition and the specific bacterial strain causing their infection.

What are the challenges?

But before we get too excited, the report outlined some major hurdles to be overcome. Unlike mass-produced pills, phages are living organisms that may need to be grown on an individual basis to strict quality standards. Current regulations simply aren’t set up to handle such a personalised medicine. We’re still in the phage-pioneering phase in the UK compared to some other parts of the world.

In a response published on 1 March 2024, the government states it is committed to engaging with the scientific community through forums like the Innovate UK Phage Innovation Network. It acknowledges the need to provide greater clarity around phage regulations, manufacturing requirements and clinical trial pathways.

Importantly, the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) will publish draft guidance later this year on the licensing of phage products, with input from researchers and industry. This should finally start clearing the fog around how phages will be regulated in the UK.

On the critical issue of manufacturing, the government says it will consider the case for developing a Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) facility that could support phage innovators. Though it can’t commit funding yet, it’s encouraging that ministers recognise the importance of this infrastructure gap. Crucially, it signals an intent to tackle some of the key regulatory and infrastructure barriers currently holding phages back.

The response also suggests the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) is open to receiving more applications for phage research funding and clinical trials. With guidance coming on trial requirements, the pathway may become clearer for phage development programmes.

The government states that phage therapy will be wrapped into the broader 2024-2029 national action plan on AMR as one of the potential solutions requiring further evidence.

How is the UKHSA working on phages?

As interest in phage therapy continues growing, having a centralised repository of phages will be crucial for supporting research and enabling wider adoption of these precise viral treatments. The UKHSA’s National Collection of Type Cultures (NCTC) is at the forefront of developments in the UK, having recently established a bacteriophage collection.

The NCTC is the world’s oldest bacterial strain library, and this new phage repository is intended to be a trustworthy source where scientists can both access and deposit phages. This dynamic collection will help drive accessibility, reproducibility and further exploration of phages’ therapeutic potential.

With a century of experience with phages already under our belts, combined with cutting-edge initiatives like the NCTC phage bank, the UK has a strong foundation to build upon. By prioritising phage research, updating regulations, and fostering a collaborative ecosystem, we can cement our position at the forefront of this exciting next chapter of using viruses to conquer superbugs.

It may sound like a big ask, but the potential payoff is huge. Phages could be a key part of the toolkit we desperately need to keep humanity one step ahead of constantly evolving superbugs.

[ad_2]

Source link